At our house in Evansville IN, the oak tree in the front lawn has been producing more acorns than I ever remember during the 22 years living here..........by a wide margin.

Some people speculate that it means a cold Winter coming up.

However, plants and animals don't have the ability to react to unique signals which tell us what the weather might be numerous months from now.

Numerous creatures can see the magnetic field, which is invisible to humans that don't have developed technology and those creatures can use it as a compass for migration in traveling thousands of miles and for other things but that doesn't tell them anything about the weather.

Acorn production also varies from location to location and tree to tree.

It can be affected by the prior years weather though. A mild Winter and great flowering in the Spring with no late freezes, followed by tons of rain would be optimal for acorn production.

Another huge plus is the increase in CO2. For every added 5 parts per million of CO2, plants, in general will grow 1% more(rapidly) and be more productive. This would contribute to MORE acorns, just as its added an additional 25% to crop production in the last century just from the added CO2.

Climate change has created more favorable conditions for all plants and most animals. You will not be getting many articles from the MSM to tell you that or focus on that being the reason for more acorns.

However, there is a natural cycle part of this too that is independent from weather and other conditions.....when this happens it's called a MAST YEAR.

More coming up.

https://blogs.massaudubon.org/yourgreatoutdoors/about-those-acorns/

Fall is a time for nuts and no nut is more noticeable than the acorn, the fruit of oak trees and food of wildlife.

Some years are boom years for acorns. Hikers dodge falling acorns and balance on trails that seem to be covered in marbles.

Other years, we seem to have no nuts.

Like many trees, oaks have irregular cycles of boom and bust. Boom times, called “mast years,” occur every 2-5 years, with few acorns in between. But the why and how of these cycles are still one of the great mysteries of science.

Scientific research can tell us what a mast year is not. A mast year is not a predictor of a severe winter. Unfortunately, plants and animals are no better at predicting the future than we are.

Strangely, mast years are not simply resource-driven. Sure, a wet, cool spring can affect pollination and a hot, dry summer can affect acorn maturation. But annual rainfall and temperature fluctuations are much smaller in magnitude than acorn crop sizes. In other words, weather variables cannot account for the excessive, over-the-top, nutty production of acorns in a mast year.

So what does trigger a mast year? Scientists have proposed a range of explanations—from environmental triggers to chemical signaling to pollen availability—but our understanding is hazy and the fact is that we simply don’t know yet.

Boom and bust cycles of acorn production do have an evolutionary benefit for oak trees through “predator satiation.” The idea goes like this: in a mast year, predators (chipmunks, squirrels, turkeys, blue jays, deer, bear, etc.) can’t eat all the acorns, leaving some nuts for growing into future oak trees. Years of lean acorn production keep predator populations low, so there are fewer animals to eat all the seeds in a mast year. Ultimately, a higher proportion of nuts overall escape the jaws of hungry animals.

Whatever the reasons and mechanisms behind acorn cycles, mast years do have ecological consequences for years to come. More acorns, for example, may mean more deer and mice. Unhappily, more deer and mice may mean more ticks and, possibly, more incidences of Lyme disease.

Many animals depend upon the highly-nutritious acorn for survival. Oak trees, meanwhile, depend upon boom and bust cycles, and a few uneaten acorns, for theirs.

Why does this happen? Mild winters can mean more acorns, as white and red oak trees are able to produce more in the spring, while harsh winters or a springtime freeze can lead to little-to-no acorn production.

https://thebotanicaljourney.com/blogs/the-botanical-journey/oaks-acorns-and-the-mystery-of-the-mast

Did you know that the Oak trees of North America produce more nuts than any other tree region worldwide, cultivated or wild?

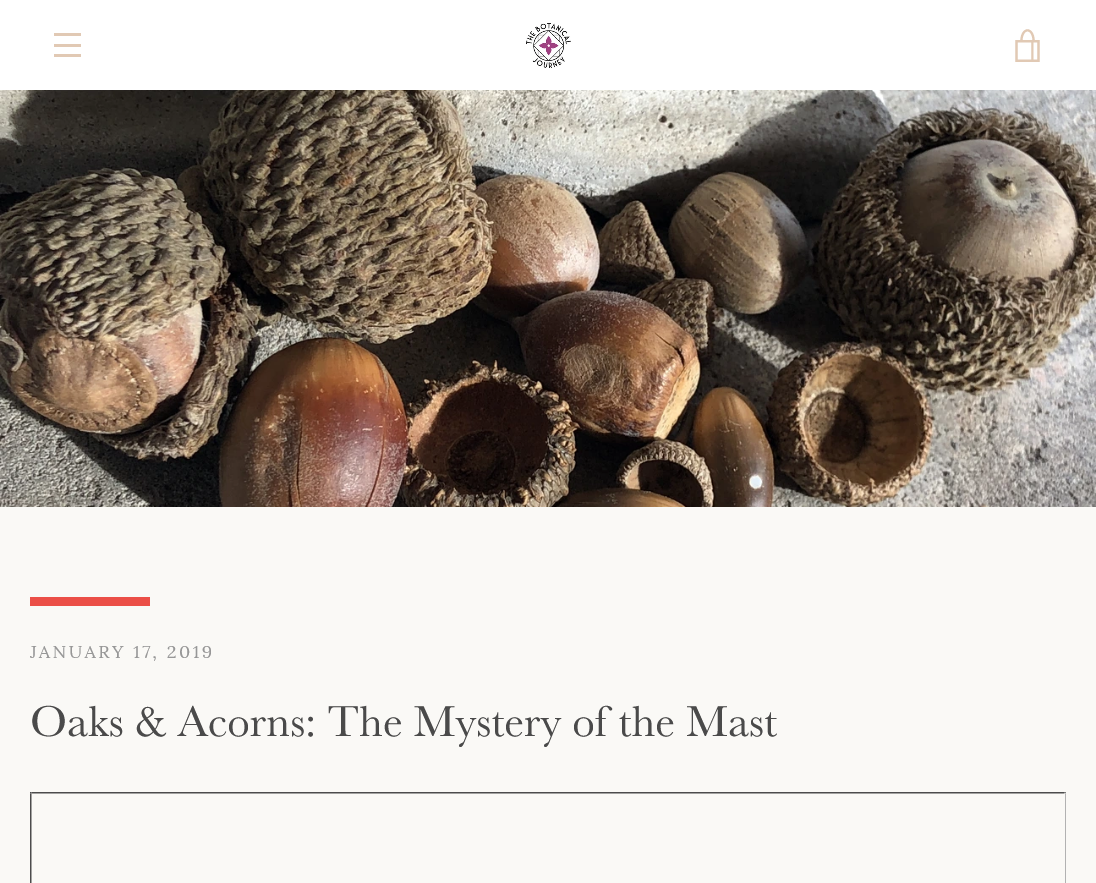

The fruit of an Oak tree is an acorn. A single giant Oak tree can produce nearly ten thousand acorns in a reproductive season. However, Oak trees do not bear fruit every year and some acorns require up to 18 months to mature. When a forest nut-bearing tree, like an Oak, Pecan, or Walnut, produces a high yield or bumper crop, the year is botanically referred to as a 'mast' year.

What is a Mast Year?

Mast is a term used to describe the fruit of forest trees and shrubs. The fruit can be hard nuts, like acorns or beechnuts, or soft, like blueberries or wild grapes, and are an important food source for wildlife. A mast year is when a particular woodland species produces more fruit than normal. Like many trees, Oaks have irregular cycles of high and low yields. Oak masting happens every 2- 5 years.

Why Do Oaks Mast?

Scientists are uncertain as to the exact reason why oaks and other plants mast but there is a range of theories from climate temperatures and rainfall amounts to harsh summers affecting acorn production or the availability of spring winds during pollination. The specific causes remain a mystery, but one undeniable evolutionary benefit of masting is... ensured future offspring.

Acorns are the easiest way to identify an Oak tree. There are over 600 species of Oak trees with more than 200 species endemic to North America. This elliptical oak shaped leaf indicates a Mexican White Oak tree and can be found growing as far south as Guatemala.

In mast years, acorns fall by the thousands increasing food availability for squirrels, mice, birds, and other forest frugivores. During mast events, dependent wildlife populations increase. The following year, the trees will bear little to no fruit due to the abundance of energy required to produce the previous year's bountiful harvest. In subsequent low to no yield years, wildlife populations decrease as food becomes scarce. Then in a mast year, the overflowing harvest will more than feed the forest critters and ensure some seeds left to grow into future oak trees.