https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pangaea

Pangaea or Pangea (/pænˈdʒiː.ə/)[1] was a supercontinent that existed during the late Paleozoic and early Mesozoic eras.[2] It assembled from the earlier continental units of Gondwana, Euramerica and Siberia during the Carboniferous approximately 335 million years ago, and began to break apart about 200 million years ago, at the end of the Triassic and beginning of the Jurassic.[3] In contrast to the present Earth and its distribution of continental mass, Pangaea was centred on the equator and surrounded by the superocean Panthalassa and the Paleo-Tethys and subsequent Tethys Oceans. Pangaea is the most recent supercontinent to have existed and the first to be reconstructed by geologists.

The distribution of fossils across the continents is one line of evidence pointing to the existence of Pangaea.

The distribution of fossils across the continents is one line of evidence pointing to the existence of Pangaea.

What was the Earth like at the time of Pangea? | History of the Earth Documentary

https://www.visualcapitalist.com/incredible-map-of-pangea-with-modern-borders/

As volcanic eruptions and earthquakes occasionally remind us, the earth beneath our feet is constantly on the move.

Continental plates only move around 1-4 inches per year, so we don’t notice the tectonic forces that are continually reshaping the surface of our planet. But on a long enough timeline, those inches add up to big changes in the way landmasses on Earth are configured.

Today’s map, by Massimo Pietrobon, is a look back to when all land on the planet was arranged into a supercontinent called Pangea. Pietrobon’s map is unique in that it overlays the approximate borders of present day countries to help us understand how Pangea broke apart to form the world that we know today.

Pangea was the latest in a line of supercontinents in Earth’s history.

Pangea began developing over 300 million years ago, eventually making up one-third of the earth’s surface. The remainder of the planet was an enormous ocean known as Panthalassa.

As time goes by, scientists are beginning to piece together more information on the climate and patterns of life on the supercontinent. Similar to parts of Central Asia today, the center of the landmass is thought to have been arid and inhospitable, with temperatures reaching 113ºF (45ºC). The extreme temperatures revealed by climate simulations are supported by the fact that very few fossils are found in the modern day regions that once existed in the middle of Pangea. The strong contrast between the Pangea supercontinent and Panthalassa is believed to have triggered intense cross-equatorial monsoons.

By this unique point in history, plants and animals had spread across the landmass, and animals (such as dinosaurs) were able to wander freely across the entire expanse of Pangea.

Around 200 million years ago, magma began to swell up through a weakness in the earth’s crust, creating the volcanic rift zone that would eventually cleave the supercontinent into pieces. Over time, this rift zone would become the Atlantic Ocean. The most visible evidence of this split is in the similar shape of the coastlines of modern-day Brazil and West Africa.

Present-day North America broke away from Europe and Africa, and as the map highlights, Atlantic Canada was once connected to Spain and Morocco.

The concept of plate tectonics is behind some of modern Earth’s most striking features. The Himalayas, for example, were formed after the Indian subcontinent broke off the eastern side of Africa and crashed directly into Asia. Many of the world’s tallest mountains were formed by this process of plate convergence – a process that, as far as we know, is unique to Earth.

Since the average continent is only moving about 1 foot (0.3m) every decade, it’s unlikely you’ll ever be alive to see an epic geographical revision to the world map.

However, for whatever life exists on Earth roughly 300 million years in the future, they may have front row seats in seeing the emergence of a new supercontinent: Pangea Proxima.

As the above video from the Paleomap Project shows, Pangea Proxima is just one possible supercontinent configuration that occurs in which Australia slams into Indonesia, and North and South America crash into Africa and Antarctica, respectively

A scientific idea that was initially ridiculed paved the way for the theory of plate tectonics, which explains how Earth’s continents move.

https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/continental-drift-versus-plate-tectonics

The story begins with Alfred Wegener (1880–1930), a German meteorologist and geophysicist who noticed something curious when he looked at a map of the world. Wegener observed that the continents of South America and Africa looked like they would fit together remarkably well—take away the Atlantic Ocean and these two massive landforms would lock neatly together. He also noted that similar fossils were found on continents separated by oceans, additional evidence that perhaps the landforms had once been joined. He hypothesized that all of the modern-day continents had previously been clumped together in a supercontinent he called Pangaea (from ancient Greek, meaning “all lands” or “all the Earth”). Over millions of years, Wegener suggested, the continents had drifted apart. He did not know what drove this movement, however. Wegener first presented his idea of continental drift in 1912, but it was widely ridiculed and soon, mostly, forgotten. Wegener never lived to see his theory accepted—he died at the age of 50 while on an expedition in Greenland.

Only decades later, in the 1960s, did the idea of continental drift resurface. That’s when technologies adapted from warfare made it possible to more thoroughly study Earth. Those advances included seismometers used to monitor ground shaking caused by nuclear testing and magnetometers to detect submarines. With seismometers, researchers discovered that earthquakes tended to occur in specific places rather than equally all over Earth. And scientists studying the seafloor with magnetometers found evidence of surprising magnetic variations near undersea ridges: alternating stripes of rock recorded a flip-flopping of Earth’s magnetic field.

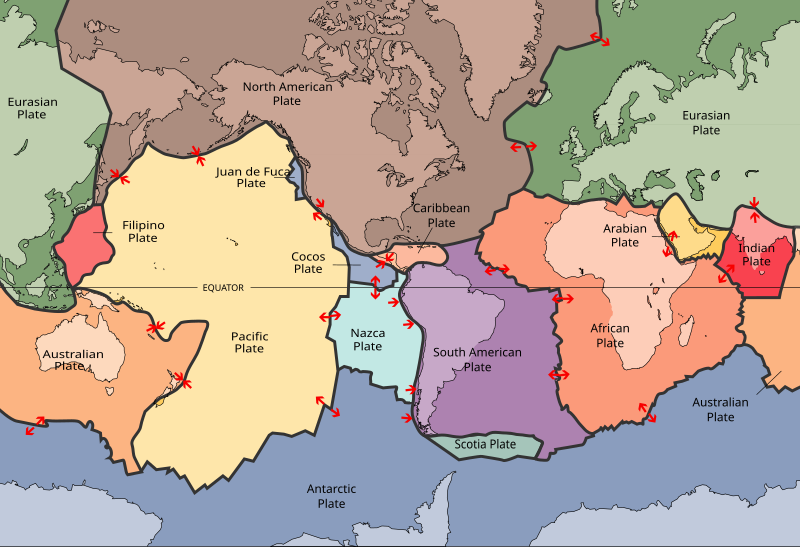

Together, these observations were consistent with a new theory proposed by researchers who built on Wegener’s original idea of continental drift—the theory of plate tectonics. According to this theory, Earth’s crust is broken into roughly 20 sections called tectonic plates on which the continents ride. When these plates press together and then move suddenly, energy is released in the form of earthquakes. That is why earthquakes do not occur everywhere on Earth—they’re clustered around the boundaries of tectonic plates. Plate tectonics also explains the stripes of rock on the seafloor with alternating magnetic properties: As buoyant, molten rock rises up from deep within Earth, it emerges from the space between spreading tectonic plates and hardens, creating a ridge. Because some minerals within rocks record the orientation of Earth’s magnetic poles and this orientation flips every 100,000 years or so, rocks near ocean ridges exhibit alternating magnetic stripes.

Plate tectonics explains why Earth’s continents are moving; the theory of continental drift did not provide an explanation. Therefore, the theory of plate tectonics is more complete. It has gained widespread acceptance among scientists. This shift from one theory to another is an example of the scientific process: As more observations are made and measurements are collected, scientists revise their theories to be more accurate and consistent with the natural world.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plate_tectonics

Simplified map of Earth's principal tectonic plates, which were mapped in the second half of the 20th century (red arrows indicate direction of movement at plate boundaries). [1]

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Diagram of the internal layering of Earth showing the lithosphere above the asthenosphere (not to scale)

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

| Geology |

|---|

| Part of a series on |

Science of the solid Earth Science of the solid Earth |

Thats a super string - thanks.

Hey Mike,

Looks like Turkey just had one of those 7.8 tectonic plate shifts!

I wouldn't want to be around if this earth decides to form another mountain range like the Rockies or Himalayans.

John